Work at the railway

I am from Kvasyliv, in the Rivne region. I worked at the railway – at the Zdolbuniv locomotive depot – as a brigadier of the battery department.

Since childhood, my hobby was shooting. Everything was connected with weapons, shooting, and the war. I dreamed of joining the army. But because of my health condition, I was not accepted. At first, long ago, I dreamed of aviation. Because my uncle was a major and he flew helicopters. Then I got a little older and the marines fascinated me. I dreamed of becoming a marine or, like most guys dreamed of becoming special forces, I wanted to do it too. I went in for judo and kickboxing.

In 2014, I was 16 years old. In 2022, during the first two days of the full-scale war, I tried to organise my relatives and take care of their safety. I recommended them to leave the country until the situation was clarified because it was not known how far the Russian troops would go. My family refused. Then I bought some basic necessities, put together a first aid kit, and explained more or less how to do bandages. And then I went to the military commissariat. I was not immediately enrolled because I had a leg injury that made me unfit for military service.

I went to work, and it was difficult to take time off, because the railway was, on the contrary, starting to work more, switching to military conditions. In addition, colleagues at work started talking about the possibility of keeping me from the army.

The second time I went to the military commissariat, but not to the queue for personal files, but to the queue with people who were going to the frontline to fight. I passed the medical examination, filled in the documents and left. At work, I made up a story that I had been stopped by the military commissariat and was drafted, so now I just had to go. At the military commissariat, I asked for a call-up to bring it to work so that it would not be considered that I was skipping work.

At that time, I had a lot of friends and acquaintances who were already in the army, some of them were in the war zone. I just could not stay at home. I considered it wrong. In addition, most of my friends were much younger than me. I hoped that I could get to the same unit with them and look after them.

I have a lot of friends from the Red Cross, and they had been constantly teaching me tactical medicine. I had been learning how to shoot a lot so I already had some skills. And my friends who have just signed a contract, what did they possibly know and were able to do? And in the end, I was older.

In the war

At first, I was trained as a grenade launcher. Then I was transferred from the training to the 46th Airborne Assault Brigade. And there I was taken aside from another line and told: “We looked at your personal file, we would like you to be a reconnaissance officer. We need scouts”. I said: “Great! It’s my dream. It would be a great honour for me to become a reconnaissance officer”. They said: “You’re the first person we’ve ever heard that from. We saw that you have been trained to be a grenade launcher, so you can become either a grenade launcher, a sniper or a machine gunner.” It’s fun to shoot a grenade launcher, but I didn’t want to carry it around. Being a sniper is a hard job, and I didn’t know if I could handle it. So I chose a machine gun.

My first combat missions were in the Kherson region, in June and July. I had no illusions about myself and didn’t expect myself to be some kind of Rambo. I realised that I did not know how I would behave on the battlefield. I might panic. The thing I was most afraid of was just freezing and remaining speechless not being able to do anything. But as it turned out, this did not happen to me. I was scared, but I could control my fear and keep on moving forward and complete my tasks.

In civilian life, I liked to play computer games. The first time we were working, it felt a bit like a computer game where you are walking and you see things on the ground: an assault rifle, ammunition, a bulletproof vest, and a backpack with things. And you expect that you’re going to go through a certain area or go around that corner and they’ll start shooting at you. And you are on the alert all the time.

Wounded, captured

I was wounded on July 19. I don’t remember much about that moment. I remember how we were walking, how the battle started, I remember how I was wounded, but I don’t remember what happened next.

We stumbled upon a russian ambush and joined the battle. First, I was hit in the chest. I felt something burning in my chest. I tried to inform my comrades about my injury via the radio, but as soon as I opened my mouth blood spurted out. Then I was hit in the legs and then a shot through the armour penetrated and injured my spine.

I was paralysed. Some of my comrades retreated, and some were killed. Another wounded comrade stayed with me.

I was taken prisoner of war. At first, they just drugged me with painkillers and tried to interrogate me. I blacked out, then came to my senses and found that I was already blindfolded. I don’t know what happened next.

It felt as if I had spent a week in captivity with my eyes blindfolded. Then another day it felt like I might have been in a coma for several years. When they uncovered my eyes I saw that I had had surgery and some wounds were bandaged. And it turned out that it was just a day since I was found and captured.

They just stabilised me so I wouldn’t die. I wondered about why I was being held captive with such injuries. But I couldn’t find an answer.

The russians liked to mock the topic of the exchange. They would come and say: “Congratulations, you are being exchanged tomorrow,” and then no one would come. And the next day, the same thing: “Yesterday it didn’t work out, but today for sure”. And so on for a month. Or they would tell you that you will be exchanged every day, and then they just take you to another hospital.

At first, I was held in Sevastopol, where there was still at least some medical care. When I was already being transported, I was told that I was leaving Sevastopol for an exchange. The documents they put on my chest indicated the city, so I found out where I was held. But I was transferred to Simferopol.

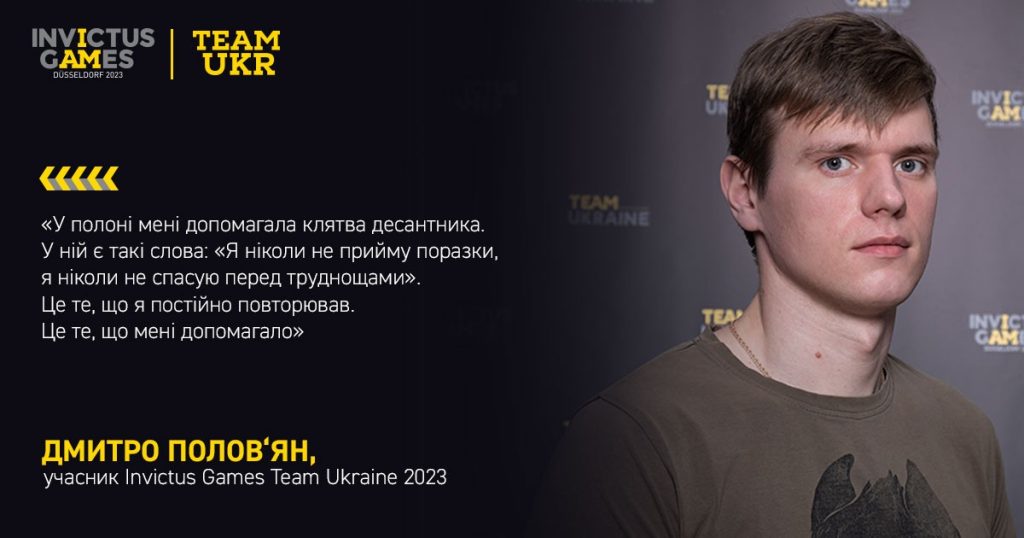

What helped to survive

The paratrooper’s oath helped me. It says: “I will never accept defeat, I will never give up in the face of difficulties”. This is what I kept repeating.

Even before the army, before the full-scale war, I often looked at the experiences of different soldiers from different countries, and how they fought somewhere. Some of them talked about how they were captured and what helped them survive. I never thought I would be taken prisoner myself, I was sceptical about it. But the British Special Forces told me that when you are captured and you have no way to counteract the enemy, you can humiliate the enemy in your mind. You have to look for visual flaws and make up some funny stories but at the same time, it’s important to refrain from showing any contempt towards them.

I imagined, for example, leaving that ward and speaking to them as if I were not their prisoner, but vice versa. Sometimes I thought that when they interrogated me about how I got captured, I should have said: “We don’t know anything, they told us we were going to the training”.(This is what russian soldiers often say when taken prisoners of war)

I wonder what their reaction would have been.

I was held in captivity from July 20 to October 13. I found out that I was released from captivity when I was loaded into our ambulance. At first, everyone spoke russian, and then they loaded me into the ambulance, and I saw a man in our uniform addressing me. I was told: “Don’t worry, you have been exchanged, we will help you. If you are in pain, tell us, and we will give you painkillers, maybe you have some other injuries…”

When I was released from captivity, it was hard. It felt like I had spent not three months, but about 30 years in a locked place. It seemed to me that everything had changed, that I didn’t know anything, I didn’t know what was going on and where. Because in captivity, the russians kept saying: “What brigade are you from? 46? But it’s gone!” or “Where are you from? From western Ukraine? We bomb it all the time”. They kept telling us that they had captured Mykolayiv and wiped it off the map.

There were always their wounded soldiers outside the door, and when they were talking to each other, I could more or less get a picture of what was happening. There was a constant flow of their recently wounded soldiers. That’s how we learnt that our troops were close to Kherson. The russians complained that our artillery was hitting them hard and that people had almost reached Kherson. And that made me feel happy. Those were the only positive moments.

Rehabilitation

It was hard at first. I didn’t want to have any contact with anyone at all, I didn’t want anyone to see me in such a condition. I had a plan to focus on rehabilitation and get back on my feet after being released and let someone visit me when I’m able to walk with crutches or a walker.

I kept telling myself: “I will never accept defeat, I will never fail in the face of difficulties,” and I planned to just keep working. This is what helped.

Three or four days later, my brother, mother and father came to see me. It was hard for me. I didn’t know what to say and didn’t know how to respond to their questions. I felt relieved just when I was left alone.

Now it all depends on the situation. For example, if I’m somewhere among people, I don’t want to be alone. I need someone familiar, someone I know and can talk and open up to. Sometimes I have panic attacks when I am among people. It seems like I am attracting everyone’s attention. That used to be a huge problem.

I had this psychological issue: when I went out into the street where there would be a crowd of people, I tried to wear a mask or somehow cover my face because it felt like everyone was staring at me. Later, I bought a mask and believed it made me just a person in a wheelchair to people. They wouldn’t know who I was.

There were instances when people took photos of me without permission. Once, while I was out, a girl and her mother were walking by and simply took a photo of me. Photography and cameras were also a problem. For over two months I didn’t allow anyone to take my picture, even when I needed to renew my passport. It was psychologically difficult for me. While I was a prisoner of war the russians used to film everything including torture and would often stick cameras in my face. But somehow I was able to overcome it.

Now if I take a walker, I can walk 100 metres. Only with the walker for now though. Some doctors and rehabilitation specialists say that I have a 100% chance of walking. There is not much chance that I will be able to run, but there is a chance that I will be able to walk with a walking stick. While others believe I need to accept the fact that I won’t walk again.

After the competition in Düsseldorf, I have a lot of plans. I need to decide whether I will stay in the service or not. I need to buy a house and a car. Finally, I need to get married. We planned to before the war, but it didn’t work out.

For a month after I was released from captivity, I just didn’t want my girlfriend to see me in such a condition. But when I allowed her to come, I didn’t regret it. I understand that it was difficult for her too. She keeps telling me: “I understand what you’ve been through”. And I keep thinking that it’s nothing compared to what she went through. I realised this all the time. I didn’t want her to suffer with me. But then she decided that it was her choice to support me, as she loves me. I’m not perfect, but I try to support her as well.

How would you describe yourself?

That’s a tough question. I have always been a realist. I was also realistic about my abilities. I clearly knew my limits. Before I was wounded, I was not very sociable. And after captivity, I had big problems with communication.

How do you like to relax?

Before the war, I liked to go to the forest, hike and go somewhere away from cities and civilization, with a certain circle of people. I liked to be outdoors with my friends. I don’t have many friends, but they are people who have been tested by time and circumstances.

How should society treat servicemen with injuries or in wheelchairs?

I have seen many different reactions. And even positive attention can sometimes feel unpleasant. Once I was in a park and a woman with a child was walking. She pointed at me and said: “This is our defender”. I felt confused. And in terms of emotions, it was something like being filmed. The attention and gratitude made me feel uncomfortable. I don’t need any gratitude, ordinary communication just like with any other person is enough. If I don’t ask for help, then I don’t need help.

When should you be helped?

When I ask for it. When I was first released from captivity, people tried to help me and felt sorry for me. I spent three months without any pity and without good emotions. I can still do without it now. It has been a motivation for me to get back on my feet and keep developing. I tell myself that I need to work and not wait for anyone to help me, and that’s it.

Who is your motivator and example?

One of them is Andriy Badarak. He got me involved in the Invictus Games. He taught me to swim and made me try it. There’s also Viktor Lehkodukh. And a lot more people.

Have you changed a lot after your experience?

A little bit. I just became more introverted. And I have more issues in my head. But you’ll have to ask my girlfriend about that.

How does your girlfriend support you?

She takes the wheelchair away and says: “Come on, don’t be lazy, work hard, I believe in you.” She is my first motivator. The second is the paratrooper’s oath, and the third is Andriy (Badarak).

What should be done to make this war the last one?

We need to change society. And we need to work very hard. It takes a lot of work to make this war the last one. We need to teach people not to be indifferent to their history. Even to the history of their native land, village, town. You need to respect what you have. To respect the land you live on, to take care of the environment, to take care of each other.

Why do you want to take part in the Invictus Games?

I liked swimming, I got interested in it. I thought, why not? For me, participation in the Invictus Games is also a way of rehabilitation. One of the ways to get rid of certain issues in my head, for example, in communication, is to fight certain reservedness. Because it is easier to communicate in a circle of like-minded people. There are many people here who can understand me and support me.