Before the full-scale war

I am a tractor driver, a gunner, and a mechanical engineer. I studied to become a mechanical engineer, and at the same time, I received a second degree as an artilleryman.

In 2015, I was mobilised to serve in the State Border Guard Service in the Sumy region. At that time, I wrote a report to serve in Kramatorsk, but I was told that there were already enough officers serving there, and I would serve in Krasnopillya.

In my youth, I was involved in athletics and sports in general. I won prizes at the Ukrainian championships and was a six-time champion. But I didn’t make it to the junior national team or further. I was 15-16 years old, so a transitional age started and I was thinking about whether to go to the training camp or study in order to keep my scholarship. I had to choose between studying and working.

I used to have a dream – to have my own house or apartment and put my medals on the wall in it. I’ve had my apartment for two years now, and I haven’t put them up yet for my child can see. Now I’m thinking about whether to build a house or not because we live 10 kilometres away from the frontline.

In 2014, there were no hostilities in our region, but we could go to the ATO zone. In 2014, everyone still called the war a “hybrid” war, and as far as I remember, in our region, instead of 10 checkpoints, only five were left. I have always admired military uniforms. But after 2015, when I saw everything from the inside, I realised that the army was not for me. I can’t do anything under the conditions: “Whoever is older – is smarter and is always right”.

Full-scale war

On 24 February, the situation was completely different. At 5:00 a.m., the missiles started flying. Our city is located in a kind of a wedge to russia. The russians were on the Konotop highway, passed Kyiv-Moscow and were going to Buryn and to Sumy, Sofiyivka, and we were 15 kilometres away from both sides. They went past us. We did not experience being under occupation or anything terrible. Some people fled, some did not, some stayed at home, and some went to Sumy.

We did not know what to expect. It was 40-50 kilometres from Sumy to the occupied Trostianets and Okhtyrka, and they are further from the border than we are. The russians set up their posts in Buryn and Sofiyivka. I took my wife and child to my grandmother’s house in the village so that they would not live in an apartment but in a private house.

For the first few weeks, it was not very clear what was happening and what would happen next. And when the russians were leaving, they went the same way through Sumy and Buryn and everything was calm again. And then the air strikes and air raids started…

On the eve of the full-scale war, on 23 February, I received a call from the military enlistment office, they said: “Come tomorrow. With your belongings”. In the morning, everyone was in a panic, it was not clear who was going where. People were standing in front of the military commissariat, but it was closed… The town is small, everyone knows each other, so people started calling each other but one could really say anything. We didn’t have a territorial defence or anything like that. There were just hunters left – somebody had a gun, somebody had a stick or something else. We were just patrolling the city and organised the self-defence group to prevent looting. Some of my friends went to defend Sumy, they stood at checkpoints.

At the military commissariat, they told me not to rush, and that everything would work out at home. And then they called and that was it: Lviv, ground forces, training, artillery…

During the distribution in Lviv, I said: “It’s not that I want to go home, but I used to serve at the border, I have experience. I would be more useful at home”. But I was sent to the 57th Brigade. And I ended up in Lysychansk.

All day long, we had targets and tasks. Six times a day we were moving around, firing Grad systems twice. Then the russians from Toshkivka and Sievierodonetsk began to narrow the encirclement and by the end of June, the Luhansk region was occupied.

When I drove through the village, children waved at me, and people smiled. And then a few days later we had to drive the russians out of that village. One farmer once asked us: “Well, guys, are we holding the defence?” I said: “Of course, we are.” And two days later, the russians pushed attacked so hard that we had to move 30 kilometres back. I was so ashamed for misleading that man. I don’t know if he moved out. But there were also cases when we were betrayed by the citizens. In Bakhmut, we still had Ukrainian mobile communication, but in Lysychansk, we didn’t, there was no service. The locals would wave to you and then take their phones and call someone, which meant they already had a russian mobile operator. And right after that, we would get hit by missiles.

After the Luhansk region, we had an operational coordination in the Chernihiv region for a month and a half. And then we went straight to Kherson. We came in at the end of August. I joined a mortar unit.

We had some losses… One driver was killed, and two soldiers were injured. I slightly objected that I was a bit out of place with a mortar there because I couldn’t reach anywhere… If I had been engaged in the artillery instead, maybe I wouldn’t have been injured… We did reconnaissance and evacuation, I did everything I could. And people wanted to follow me. Somehow we worked and did everything in a hurry.

Injuries

In Odesa, I found out that four people had been blown up on mines in the same forest. And all of them had left leg injuries. We all laughed at it.

There are a lot of mines there. When we went beyond the Ingulets River, into the russian trenches we saw that their positions were cleverly made, and the wires were stretched. I had to scout the area a bit. And not only was everything covered with leaves but there were explosions and gunfire around, so I couldn’t really look where I was walking. I stepped on an anti-personnel mine. At first, I thought something had exploded nearby. And then everything went numb, I felt the heat in my legs. I looked… “That’s it,” I thought, “the war is over. I applied a tourniquet. Andriy was shouting that he was going to pull me out, and I told him to try a rope so that he wouldn’t blow himself up too.

When we were driving I felt my flesh stinking. It was clear that the leg was gone there were just pieces hanging. When we were on the way to the hospital in an ambulance, there was an infantryman whom I had evacuated with a contusion earlier that morning. He was very surprised to see me.

At first, I was sent to Berezneguvate, the Mykolaiv region. They performed an amputation there. The next day I was sent to Mykolaiv, and from there to Odesa. And after 10 days, when everything healed a bit, I had a re-amputation.

I told my wife for several days that it was just an explosion nearby. I was given such strong painkillers and I was so “high” and I felt so good, that I could go back to war.

Rehabilitation

Somehow, I managed to adjust myself the way that I didn’t feel depressed. I watched some videos on the Internet and realised that I was not the first one. I’ve had leg surgeries before, so was familiar with the rehabilitation process.

The first six months before the prosthesis, then the application of the prosthesis and the rehabilitation were easier to cope. And now everything seems to be fine, but sometimes I feel down. I noticed that when I overstrain myself, I start feeling the nerves on the missing leg.

What helps you mentally?

I used to have a pretty active life. I used to ride my bike and went to Poland to work. But now I stay at home for days and it’s hard. I sold my tractor, I have got nothing to load. Half of the fields are mined, and half are rented out. I need to occupy myself with something. I used to go to the gym…

What do you want to do next?

I know my artillery occupation well, and I think the war will not end very soon. I was told that I could still serve with a disability. And civilian life is difficult now.

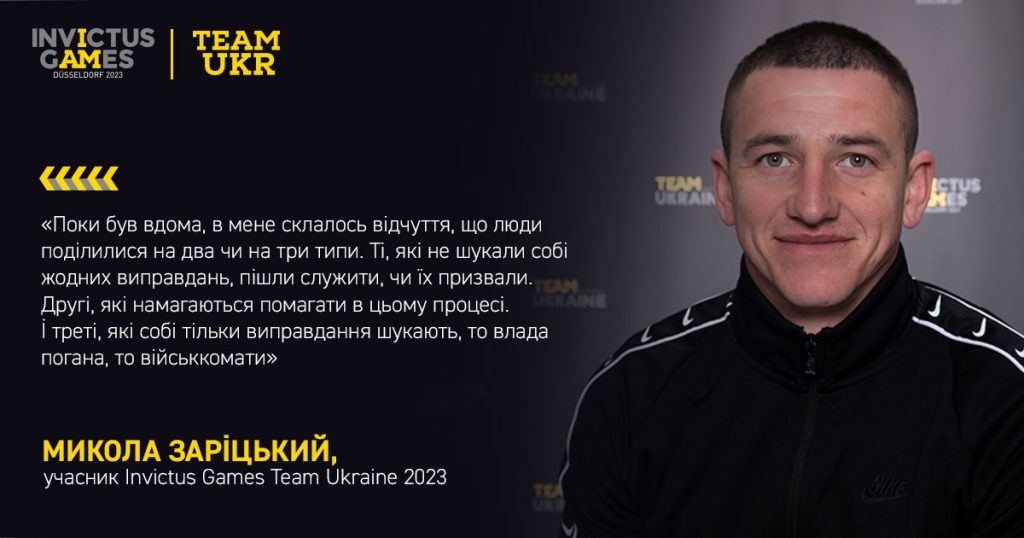

While I was at home, I got the feeling that people were divided into two or three types. Those who weren’t looking for any excuses and went to serve voluntarily or were drafted. The second is those who are trying to help. And the third type is those who are only looking for excuses, either the government is bad or the military commissariats are not good. It makes me angry to hear such things from my friends. They shouldn’t say that at least not in front of me.

Are you a pessimist or an optimist?

I don’t know. Sometimes I take psychology tests, and it seems that if I answered honestly, I would be already in a mental institution somewhere.

What do you want most for yourself right now?

Something to do with sports. I have always liked it.

Why do you want to take part in the Invictus Games?

Perhaps in my youth, I didn’t realise myself enough, so I would like to go somewhere to compete, to show what I’m worth and demonstrate good results.